Without a doubt, the sexiest new siding being used on the front of houses is stone siding. I say stone siding because that's what everyone calls it, but what I'm really referring to is Masonry Veneer. This is a man-made product that's meant to look like stone siding, and is installed in a similar manner to stucco.

While masonry veneer looks great, it's susceptible to the same moisture problems that stucco is. Moisture testing experts in the Twin Cities agree that this product has experienced the exact same type of moisture intrusion problems as stucco. Building science expert Dr. Joseph Lstiburek actually calls this product "lumpy stucco," because that's essentially what it is.

While newer stucco installations are done quite well, the folks installing masonry veneer seem to have a lot of catching up to do on proper installation details. When I inspect masonry veneer, I use the Masonry Veneer Manufacturers Association's installation guide, which you can find here - MVMA installation guide. This guide is packed with diagrams showing how to install the material, based on generally accepted methods.

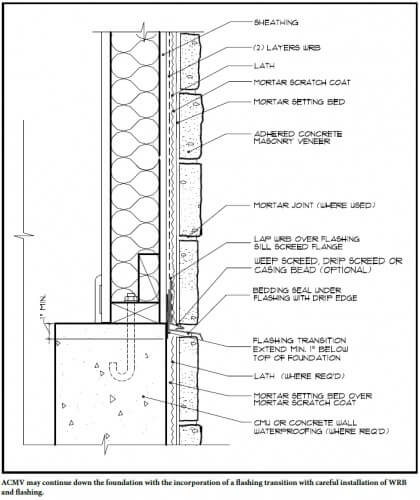

I find the same installation shortcomings over and over. To help illustrate these issues, I've taken several installation diagrams from MVMA's guide and edited them down to more clearly illustrate where the installations went wrong. As a home inspector, I don't get to see all the different layers of materials that get installed behind the masonry veneer; my inspection is limited to what I can see on the surface, and that's what I report on. To make the installation diagrams easier to understand, I've removed the labels of all the components that aren't visible during the course of a home inspection.

Too close to grade or hard surfaces

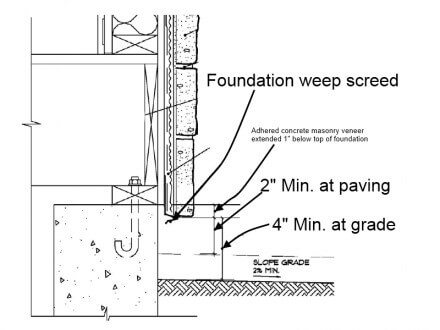

Masonry veneer should be kept at least 2" above hard surfaces, such as concrete, and 4" above the soil.

When the material is buried in dirt, water can wick up in to the material and cause rotting at the wall.

There should also be a 2" gap to paving, but this is rarely done – especially on columns.

Of course, leaving a 4" gap at the ground isn't the prettiest looking thing in the world, but there is a solution; simply have the weep screed terminated at least 4" above the ground, and have another layer of masonry veneer installed below it, as shown in the diagram below.

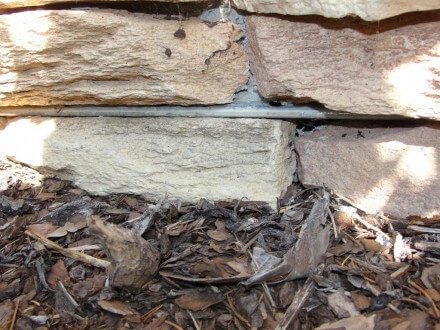

The photo below shows this detail done properly.

Here's a close up – note the weep screed.

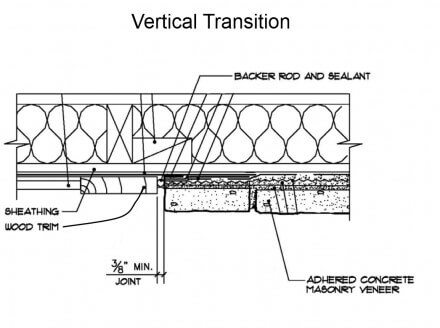

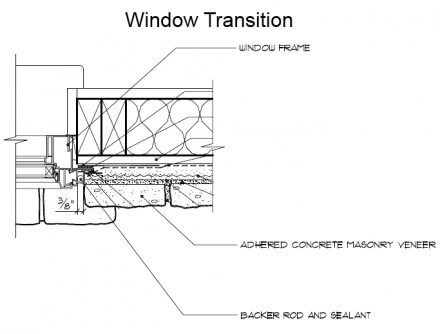

Improper Vertical Transitions

When masonry veneer has a vertical transition to something like wood trim, windows, or other siding materials, it should have a 3/8" gap left between the two different materials. This gap needs to have a foam backer rod pushed behind it, and then filled with sealant to help prevent water intrusion. This is rarely done.

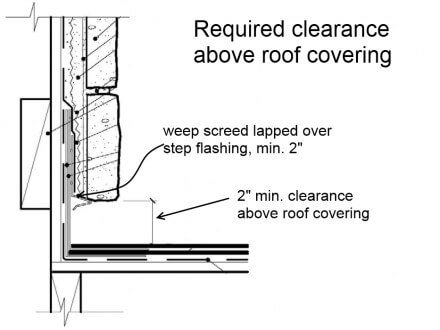

Clearance to roof coverings

Masonry veneer needs to be kept 2" above roof surfaces to help prevent water from wicking up in to the wall. The photo below shows a common deviation, where the masonry veneer actually touches the shingles. This is just asking for trouble.

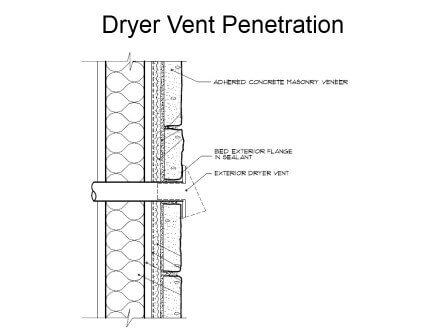

Improper Vent Penetrations

Dryer vents, kitchen exhaust vents, bath fan vents, and other similar vent terminals should be pushed up against a bed of sealant, but they're often buried in masonry. What happens when the vent cover gets broken and needs to be replaced?

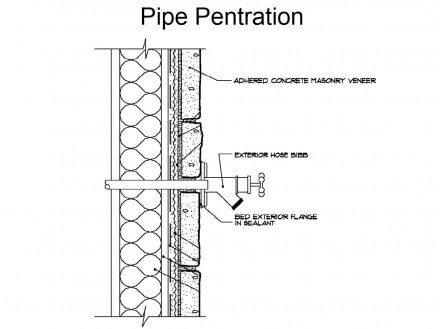

Improper Sillcock Installations

Just like dryer vents, exterior sillcocks (aka – faucets or hose bibs) need to be embedded in sealant on the surface of the masonry veneer, not buried behind the veneer. What happens when the faucet needs to be replaced?

How many bloody knuckles will this installation cause?

The nice thing about the installation shown above is that they got the vertical transition correct – check out that thick bead of caulk.

Of course, this is only a partial list of the things that can go wrong on a masonry veneer installation. If you're planning to have this material installed on your home, make sure the MVMA's installation instructions are followed to help lower the potential for water intrusion. If you're buying a home with masonry veneer already installed, treat it the same way you would stucco – consider having invasive moisture testing done.

Reuben Saltzman, Structure Tech Home Inspections